Last month, we spoke to some of the parents behind our Special Named Funds about why they choose to fund research. This week, we’re hearing from Professor Suzanne Turner about another powerful way families can make a difference – by getting involved directly.

Suzanne is a leading expert in childhood lymphoma at the University of Cambridge and currently leads eight CCLG research projects, including two funded by Special Named Funds. Recently, she welcomed families into her lab to share her work and learn from their experiences.

We also spoke to two CCLG Special Named Fund mums, Julia and Lisa, whose daughters Lila and Annika were diagnosed with anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Their fundraising has supported Suzanne's work and, determined to make a difference, they also share their lived experience of ALCL with Suzanne to help shape research.

Here’s what Suzanne had to say…

Annika's Challenge

Annika's Challenge

Annika was two years old when in April 2019 she was diagnosed with ALCL. Lisa set up Annika’s Challenge to raise funds for research into finding kinder treatments for ALCL, with fewer short- and long-term side effects.

Lila's Pink Bunny Fund

Lila's Pink Bunny Fund

Lila was eight months old when in June 2017 she was diagnosed with ALK-positive ALCL. Julia established Lila’s Pink Bunny Fund to raise money for research into ALCL.

Your Special Named Fund projects focus on a type of lymphoma. Can you explain a bit about what lymphoma is?

We’re working on ALCL, which is a cancer of the immune system. In particular, it affects the T cells of the immune system, which are the cells which normally protect us from infection. In the case of lymphoma, they've become out of control, and they can develop tumours wherever there are clusters of lymph nodes - in your neck, groin, behind your knees. Basically, anywhere where there are lymph nodes, you can get this form of lymphoma. It can also sometimes present in other places in the body like the liver or skin.

Do we know what causes it?

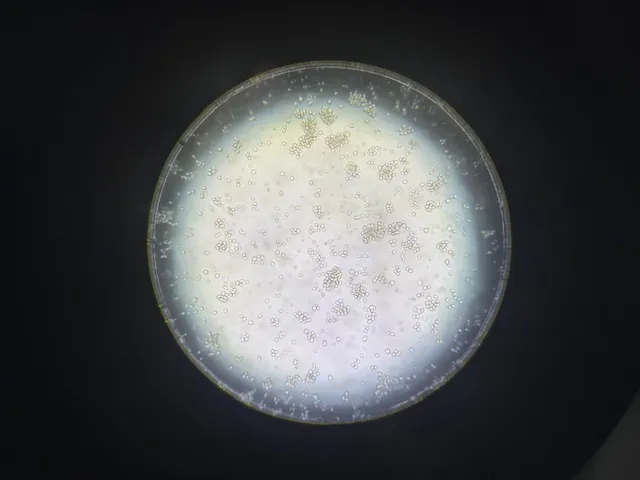

We know that most children with ALCL have a mutation in their DNA code, which drives their cancer. It happens when two different chromosomes are broken apart and put back together incorrectly, which can occasionally happen when cells are trying to repair or copy DNA. This leads to areas of DNA being swapped between chromosomes. In ALCL, where the chromosomes join up incorrectly, you end up with a new gene called nucelophosmin1-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Then, because the gene is in the wrong place, it gets switched on when it shouldn't be, and this causes the T cells to grow out of control.

ALCL cells under the microscope.

We don't know what causes that error to occur. We think it probably happens very, very early in life, perhaps in utero. Of course, that's not due to anything the mother did during pregnancy; it's just a random event. But only having this mutation doesn’t cause lymphoma – we think there’s also a second trigger after birth that develops the pre-cancerous mutated cells into lymphoma. We think that could be some sort of abnormal response to an infection, but we really don't know that at the moment.

Why does knowing about the ALK gene help?

We know that if we inhibit or ‘turn off’ the activity of ALK, we can kill off the cancer cells. And lots of ALK inhibitors have been developed to do that - just unfortunately not with children in mind. They were only approved in the UK for adult lung cancer for the first time in 2012, despite scientists first discovering ALK in 1994 in ALCL.

There are now three generations of ALK inhibitors, which can be very effective. But cancer cells can change in response to treatment, like acquiring more mutations in the ALK gene that make them resistant to one drug. The third generation of inhibitors is exciting because it can turn off forms of the ALK protein which are so mutated that they've become resistant to the first-generation drugs. However, the cancer can still adapt further. This does sometimes mean that the cancer cells then become sensitive to one of the different ALK inhibitors again – even if the cancer had previously been resistant to that drug. So, patients can essentially cycle through these inhibitors as their disease changes.

Suzanne presenting her research.

We know this happens in lung cancer, though we don't fully understand the reasons for it. But we're not 100% sure whether this also occurs for children with ALCL, because there has been limited research on the use of these drugs in children.

How are you hoping to address this?

In our CCLG Special Named Fund project, we want to see how ALCL tumours react to ALK inhibitors. So, we're trying to make a model of childhood ALCL that we can then treat with the ALK inhibitors.

We’re using our patient derived xenografts (PDX), which is where you use mice to grow human tumours. These mice have no immune systems, so don't reject the human cells. If I put the human cancer cells into a normal mouse, it would reject the cells as can happen with organ transplants. So instead, we take an immunodeficient mouse, implant tumour cells which have come from a patient, and then we can study the biology of those cells in a body setting. This allows us to look at all sorts of other things that are happening in a body, as would be in a child, rather than growing cancer cells in plastic dishes, which don’t reflect how complicated tumours and bodies are.

We know that tumours are complicated and that they aren’t all made up of the same cells. All the cells in a tumour will be slightly different, and that’s why treatment doesn’t always work.

Treatment might leave behind cells which are maybe less fast-growing or aggressive, but they can then grow back and become the dominant cell type of the tumour.

We want to look at this interaction between the different cells. So, we’re labelling all of the tumour cells with a ‘barcode’, a bit like how things in shops have their own barcodes that identify what they are. In cells, the barcode is a short bit of unique DNA we add that then gets inherited by every cell that is developed from that cell thereafter. This means that we can then track individual cells as they change in response to therapy, and we can look at the dynamics of how those tumour cells grow up or die off in response to ALK inhibitors.

Currently, although we’re using the ALK inhibitors and they do keep the tumour at bay, we know that stopping ALK inhibitors often means that the tumour grows back. So, there's clearly a group of cells that we're not killing with the inhibitors.

Essentially, that's what we want to find - what population of cells is surviving treatment, what's enabling them to survive, and then how to prevent that from happening.

How has the support from Special Named Fund families made a difference to your work?

We simply wouldn't be able to do our research without support from the Special Named Funds. The funds for this project all came from the families and friends of children with ALCL, some of whom survived treatment and, unfortunately, some of whom didn't. Paediatric cancer research is underfunded, particularly the paediatric cancers which are considered to have good survival.

When your child is diagnosed with cancer, your whole world changes overnight. You realise how rare it is, how little research there is, and how urgently more needs to be done. I set up Annika’s Challenge because no child should have to face this disease without the best possible treatments and the hope that comes from new discoveries. More funding means more research, more options, and ultimately, more children are getting to grow up. There were very few studies looking into ALCL and when Annika kept relapsing on current treatment protocols, I knew we had to help with funding to drive research.Lisa, Annika's mum and lead of Annika's Challenge

In ALCL, the survival rates are over 80%. But we're still treating children with toxic chemotherapy, which leaves them with all sorts of short and long-term side effects. Children may be cured, but they end up with all sorts of problems due to the treatment, and that shouldn't happen. We should be able to use the new targeted treatments that don't have those side effects, so more research is needed there.

Without the support of the funds and the understanding of the families who know that this is an area of clear unmet need, we wouldn't be able to do this research.

Our daughter Lila has faced three relapses, and her survival relies on therapies developed for other cancers, which have not been trialled on children. We established Lila's Pink Bunny Fund to fill this critical gap - a Special Named Fund at CCLG dedicated to raising funds specifically for paediatric ALCL relapse research, aiming to develop new cures and kinder treatments, with the hope that no other child will have to endure what we are facing.Julia, Lila's mum and lead of Lila's Pink Bunny Fund

Earlier this month, you invited families into your lab - what was that like for your team?

We really wanted to learn from the families of children on ALK inhibitors what their experiences are. The literature says that these drugs are well tolerated, you can take these drugs for the rest of your life and it won't affect you too badly. But we learned that the real-world experience of patients is very different from that. There are side effects - not just physical side effects, but also psychological side effects, and the families struggle on a daily basis due to these issues.

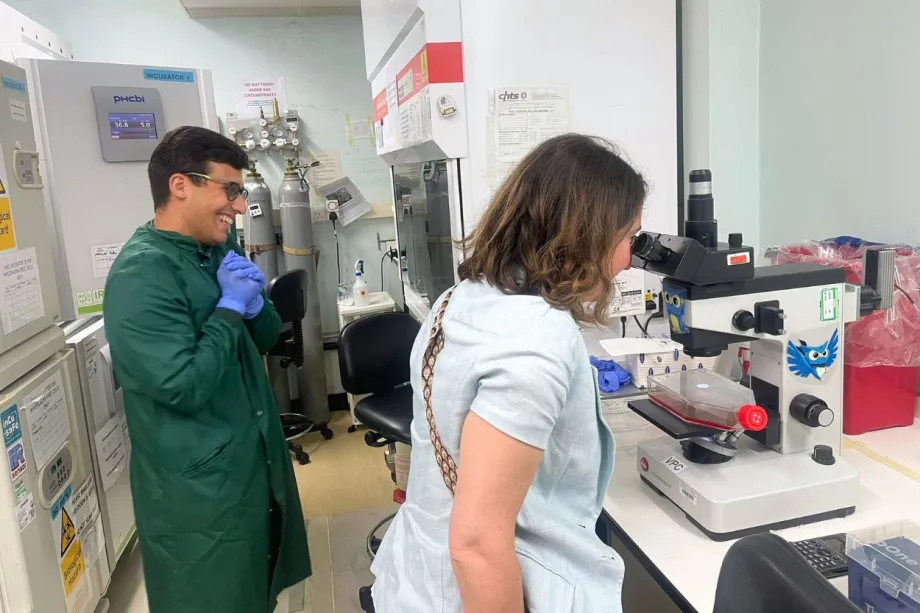

Attendees at the lab visit in Cambridge.

The families have to find ways to cope with this. It’s not just coordinating hospital appointments and fitting them in with other children in the family, and school runs and everything else they need to do. Parents essentially become ‘mum oncologists’, which is the term that they used. They have to really learn about the disease to be able to manage it from home, and to be well-informed about what might be good for their children. And because this is a relatively rare disease, parents also can play a role in informing their doctors about ongoing research.

So, the lab visit was very much a two-way process – for us to learn from them about their experiences and what the issues they see are, and for them to learn what we're trying to do in our research. It’s really useful for us to get feedback on whether we're heading in the right direction, and perhaps where we need to change our research to address the real day-to-day problems that families face.

Suzanne is achieving incredible results in her lab, giving us real hope that new treatment options can be developed and brought to clinical trials - options that could one day help Annika. Visiting her lab and meeting the amazing team working alongside her was emotional, inspiring, and fascinating, especially seeing all the different components that go into their research. I believe they also gained a lot from meeting us - the mums and the patients - and hearing our stories first-hand.Lisa, Annika's mum and lead of Annika's Challenge

Can you tell us about the roles that Special Named Fund parents on your research team play in your research?

Julia and Lisa are both mums of two little girls who have ALCL who are being treated with ALK inhibitors. Their Special Named Funds, Annika’s Challenge and Lila’s Pink Bunny Appeal, helped fund this project, and they are also part of our research group. They came for the lab visit, and they are coming back in September to speak to a European community of researchers working on ALCL. They’re going to share their experiences with ALK inhibitors with students and researchers.

Julia observing ALCL cells through a microscope.

It’s really important that we all have that patient perspective, not just because it helps us to focus on the key issues we need to address in our research, but also to get feedback on the research that we are doing. Often, the questions that we get asked by people like Julia and Lisa are very well-informed questions, which really make us think.

As well as sharing their experiences, Julia and Lisa also help with our grant writing. So, when we apply for research funding grants, they read through copies of our plans, and give us advice and help in writing the grants. This really helps us shape the research to fit the needs of the children.

With eight years of experience navigating paediatric ALCL as a parent, I felt I could contribute valuable insights to help guide her work in a direction that would best serve children affected by the disease. The parents involved in Suzanne’s Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) team represent more than 200 families from an international ALCL parent and carer online forum. Over time, this forum has become a vital source of support and information-sharing, empowering parents to advocate for their children. We hope the PPIE will amplify their voices and, in turn, offer them hope.Julia, Lila's mum and lead of Lila's Pink Bunny Fund

Finally, what message would you like to give to families who are fundraising for research?

I want to say that I really admire their strength and perseverance to do this in times of real adversity within their families. We truly appreciate everything they're doing to raise funds for research, and that progress wouldn't be possible otherwise.

Ellie Ellicott is CCLG’s Research Communication Executive.

She is using her lifelong fascination with science to share the world of childhood cancer research with CCLG’s fantastic supporters. You can find Ellie on X: @EllieW_CCLG