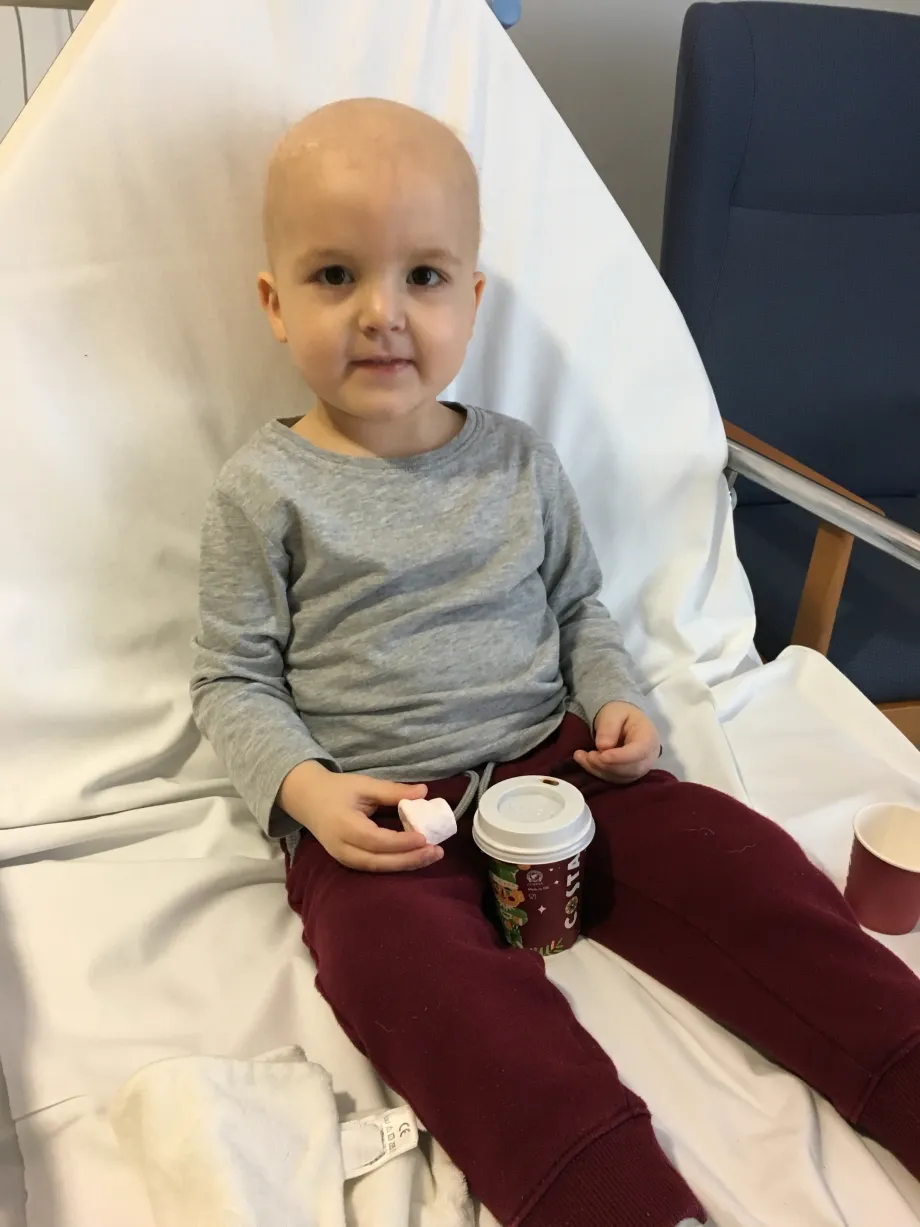

Before his diagnosis, Sebby had been unwell for a few weeks with viruses and sick bugs, but we’d assumed it was because he’d just started nursery. Then, he started to get nose bleeds, night sweats and eventually spots behind the knee and under the arms. We went to the GP who sent us straight to our local hospital for a blood test and we were told he had leukaemia soon after. Two days later, he was transferred to the Royal Marsden, where his diagnosis was confirmed.

Sebby during treatment

He had all sorts of chemotherapy, and a lumbar puncture under general anaesthetic every 12 weeks to inject chemotherapy into his spinal fluid. The community nurses visited him at home or school once or twice a week to do a blood test. He had a portacath fitted in his chest so drugs could be administered and blood taken easily.

Sebby was immunosuppressed for the whole three-and-a-half-years of treatment, so was vulnerable to infections. If he spiked a temperature of 38°C, we had to get to hospital within an hour, and he was treated with intravenous antibiotics. He had a course of steroids for one week out of every month and took oral antibiotics throughout his treatment.

The impact of treatment on children and their families is huge. Life changed for all of us when Sebby was diagnosed. It's particularly hard for siblings, who are often left behind. Sebby's older brother, Xander, was four when Sebby was diagnosed. He was old enough to know that something serious was happening, but not old enough to really understand. Sebby's younger brother, Toby, was only a few weeks old, and pretty much grew up in hospitals for the first few years of his life.

We couldn't go abroad and the holidays we did have in the UK were often cut short when Sebby was unwell. This was hard on everyone. His fifth birthday party was cancelled when he wasn’t well enough to come out of hospital, and he spent Christmas Day in hospital one year, which was tough.

Involving people with lived experience in shaping research helps ensure that information flows in both directions between researchers and patients.

Having experienced first-hand the devastating impact a childhood cancer diagnosis has on a family, I knew I wanted to make a difference for others navigating a similar path in the future. That’s why I joined CCLG’s Patient and Public Involvement Group in 2020 to have a say in the future direction of research. Through joining this, I was able to help shape the new CCLG research strategy, which will hopefully make a huge difference to what research is done in the next five years. Its aim is to help to focus and coordinate the brilliant work done by researchers, which highlights CCLG’s unique role in being able to direct research to the priorities and fill the gaps.

Involving people with lived experience in shaping research helps ensure that information flows in both directions between researchers and patients. It means researchers can focus on what matters most to patients and affects their lives during treatment and beyond. And it means patients and families can be reassured that the right research is happening and they’re being listened to.

Sebby’s now 11 and doing well. He still suffers from some side effects of treatment, but overall, he's great. He’s loving life at school and with his friends.

As for us, we now appreciate all the little wins. For example, when he takes part in a running race in sports day at school it feels like he's come so far from the time in treatment when he had to learn to walk again. Having experienced the low times through treatment, we’ll never take anything for granted.

From Contact magazine issue 109 | Winter 2025